Happy New Year!

- Saizen Tours

- Jan 3, 2021

- 8 min read

Happy New Year! あけましておめでとうございます!

2020 was a year that tested and challenged us all. So, let us bid goodbye to the Year of the Rat and look forward to the Year of the Ox – this year gives us positivity, honesty, loyalty and strength; bring on its element of earth, representing stability and nourishment. We wish you and your family a happy and healthy Year of the Ox as we stay positive and wait patiently for the day when Australia’s borders open and we can look forward to travelling overseas again.

HATSUMŌDE ~ FIRST NEW YEAR SHRINE VISIT

Hatsumōde 初詣 is the first shrine visit in the New Year. Before the clock strikes midnight there are long lines of people at major shrines and temples, patiently waiting to worship and ring in the new year. Shinto shrines are more commonly visited however visits to temples are also popular. People begin arriving a few hours before midnight on the evening of the 31st December often with large crowds arriving very early at the most famous shrines in Japan.

I took the above photo a few years ago at Yasaka Shrine, Kyoto. We arrived at 10pm and the photo was taken at 1am. As can be seen, we were still a long way from the shrine entrance! Over the years I have visited a number of shrines for Hatsumōde in Tokyo, Narita, Kyoto and Hida-Takayama, with my preference being the alps for a less crowded and local experience. At Takayama the snow was gently falling as we trudged through the streets at midnight to visit the neighbourhood shrine. Large bonfires were burning to keep everyone warm, hot sake was freely handed out and we joined the short lines to pray, be blessed by the shrine priests and then take turns to ring the huge bell for good fortune.

Some of Japan's most popular shrines and temples to visit during the first 3 days of Hatsumōde are:

1. Meiji Jingu Tokyo – 3.2 million visitors

2. Kawasaki Daishi Heikenji, Kanagawa – 3.1 million visitors

3. Naritasan Shinshoji – 3 million visitors

4. Asaksua Sensoji Tokyo – 2.8 million visitors

5. Fushimi Inari Taisha Kyoto – 2.7 million visitors

6. Sumiyoshi Taisha, Osaka – 2.6 million visitors

7. Atsuta Jingu, Aichi – 2.3 million visitors

8. Hikawa Shrine, Saitama – 2.1 million visitors

9. Dazaifu Tenmangu, Fukuoka – 2 million visitors

FORTUNES AND GOOD LUCK CHARMS

Traditional Japanese lucky charms, called Omamori お守り, are sold throughout the year at temples and shrines but are particularly popular at new year. The omamori is a small brocade pouch that contains paper or wood inscribed with a sacred text or sutra that has been blessed. They come in a variety of colours depending on the type of blessing. Popular omamori include health, wealth, education, traffic and love. Since it is a customary to bring old omamori from the previous year back to the shrine or temple to be ceremonially burned then Hatsumōde is the perfect time to purchase a new omamori.

Omikuji おみくじ are fortunes written on a strip of paper. Usually these are only in Japanese however these days some temples and shrines in major cities may also have English omikuji. Many people start the new year by checking their fortune with an omikuji on New Year’s Day. To obtain an omikuji you place a ¥100 in the donation box and then shake another box with tall sticks. Chose a stick and read the number on the stick. Replace the stick in the container and then take your fortune from the drawer with the corresponding number. If you receive a bad fortune do not keep it! Tie your fortune to a pole or a tree and leave it at the temple.

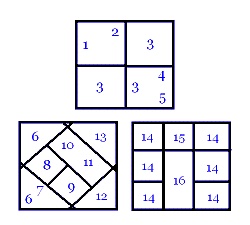

• (大吉): great blessing

• (中吉): middle blessing

• (小吉): small blessing

• (吉) blessing

• (半吉): half-blessing

• (末吉): future blessing

• (末小吉): future small blessing

• (凶): curse

• (小凶): small curse

• (半凶): half-curse

• (末凶): future curse

• (大凶): great curse

Ema 絵馬 are small, wooden plaques used to write prayers or wishes. The word Ema is written with two kanji, literally meaning ‘picture horse’ as horses were believed to carry messages from the gods. In the past horses were also donated to shrines in order to seek good blessings. Horses are expensive commodities therefore visitors would often instead leave wooden plaques with images of horses. Gradually smaller plaques could be purchased to leave wishes at the shrine or temple. These days the Ema can be purchased in a variety of shapes and designs. Once Ema are purchased (¥500 ~ ¥1,000) pens are provided to write a wish on the blank side and the Ema are then hung on a specially dedicated board in the shrine or temple grounds. Common wishes are for health, family, love and success.

DARUMA DOLLS

The Daruma 達磨 is a hollow, round, traditional Japanese doll, modelled after Bodhidharma who is the founder of Zen Buddhism. The Daruma doll has no legs or arms as a reminder of Bodhidharma losing his limbs in his quest to reach enlightenment through self-sacrifice and meditation. The Daruma is designed to be impossible to tip over as they always roll back into an upright position. For this reason the doll serves as a reminder than no matter how many times one could get knocked down, one must always endure and stand back up in order to achieve a goal. Related to this is the Japanese expression nanakorobi yaoki, which loosely translates into “seven times down, eight times up”. Thus in Japan the Daruma has become a symbol of luck and perseverance to never give up! The Daruma is purchased at New Year and a wish is made and one eye painted on. The Daruma is then place where it can be seen daily in your home or at work. Once your wish or goal has been achieved the other eye is painted on. Write your wish on the back of the Daruma and return it to the temple for burning at New Year. A new Daruma can then be bought and the cycle is repeated.

OTOSHIDAMA MONEY ENVELOPES

One of the most exciting traditions at New Year for children is receiving gifts of otoshidama おとしだま envelopes containing money. These are given in the first few days of New Year from the 1st to the 3rd January. Children usually receive the otoshidama envelopes from adult relatives, neighbours and friends up until they graduate from high school. Envelopes are usually purchased in bulk with a large range of designs, from elegant designs to zodiac animals to popular cartoon characters. New notes are usually obtained from the bank and the notes are folded into three before placing into the otoshidama envelopes. The amount given varies depending on the age of the child and the giver's relationship with the child. Average amounts are from ¥2,000 for younger children to ¥5,000 for high school students.

NENGAJŌ NEW YEAR CARDS

In Western societies we traditionally send Christmas cards at Christmas time. In Japan the tradition is to send new year greeting cards called nengajō (年賀状) or new year postcards called nenga-hagaki (年賀はがき). The custom began in the Heian Period (794-1185) when the noble class would send letters to people whom they could not meet personally to give new year greetings. As Japan modernised during the Meiji Restoration (1868~1912) its postal service was developed and the new tradition of sending New Year cards flourished.

Today postcards are sent to everyone to show gratitude and thank them for the past year and future year. So, who is everyone? Basically everyone you have an association with …..…. friends, family, neighbours, work colleagues, acquaintances, clients, teachers ……. the list goes on!

Millions of cards are posted in time for a 1st January delivery. Remarkably Japan Post accepts all cards marked with the New Year greeting ‘nenga’ (年賀) and holds these post cards to be delivered on New Year’s Day. Cards can be posted and held by the post office from 15th December to 25th December to ensure a New Year’s Day delivery.

OSHŌGATSU-KAZARI NEW YEAR DECORATIONS

Before the New Year decorations are put up Oosōji (大掃除), the big clean-up, is done.

In the lead up to the New Year the house is ‘spring cleaned’ inside and out. Then it is time

to decorate the house with the new year decorations, oshōgatsu-kazari (お正月飾り). The decorations are put up in order to win favour with the gods such as Toshigami. These decorations are said to be temporary dwelling places of kami (gods) and are usually put up from mid-December. It is best to decorate well in advance of the new year and not to rush them, or else it is believed it would anger the kami and bring bad luck.

There are usually three types of oshōgatsu-kazari - kadomatsu (usually sits at the house entrance and consists of three pieces of bamboo and some pine leaves), kagami-mochi

(a decorative stack of two tiers of mochi rice cakes with a tangerine on top), and shimekazari (a New Year’s wreath which looks similar to ancient prayer ropes).

HAGOITA NEW YEAR DECORATIONS

Hagoita (羽子板) are wooden paddles used to play hanetsuki, a shuttlecock game similar to badminton. The hagoita were introduced into Japan during the Muromachi period (1336-1573) from China’s Ming Dynasty. Gradually they were decorated with images of kabuki actors, then geisha and sumo wrestlers and these days some feature popular actors or cartoon characters. Playing with hagoita is thought to sweep away evil spirits therefore they are sold as decorations and lucky charms for the new year.

Over time, hagoita were not only used to play games but also as popular gifts and collectibles. Every year on December 17th to 19th the Hagoita-Ichi Fair has over 50 stalls at the front of Asakusa Sensō-ji Temple. The stalls sell a large variety of hagoita and other new year decorations. The fair attracts a large number of customers and also marks the end of the old year and the beginning of the new year.

TOSHIKOSHI SOBA NOODLES

Soba restaurants around the country are busy making soba on New Year’s Eve for the traditional meal called Toshikoshi Soba (年越し蕎麦). Many restaurants are open from midnight on New Year’s Eve in order to cater for worshippers after they have been to the shrines and temples. The buckwheat soba noodles are kept long to symbolize wishes for

a long life. Soba also has the symbolism of letting it go (nagasu) - as you swallow the long noodles you can forget about everything you’ve been through this year and move on to the new year. Perhaps we should all be eating Toshikoshi Soba to move on from 2020!

OZŌNI NEW YEAR SOUP

This soup dish contains mochi rice cakes and is an auspicious meal eaten on New Year’s Day as it is believed to bring good luck.

Ozōni (お雑煮) is thought to have originated as a meal that was cooked by samurai on battle fields. The broth was boiled together with mochi rice cakes, vegetables and other ingredients.

The tradition of eating zōni on New Year's Day dates to the end of the Muromachi period (1336–1573).

These days the soup is made with a light miso or kombu dashi-based broth with the important inclusion of mochi rice cakes. Other ingredients such as chicken and seasonal vegetables vary depending on the household and the region in Japan.

Be sure to chew each mouthful carefully as it is known to cause a number of deaths each year due to choking on the mochi, particularly with elderly people.

OSECHI RYŌRI

Osechi ryōri (お節料理) is believed to have first been prepared in the Heian Period (794~1185). Traditional New Year food is prepared in layered lacquer bento boxes called jubako. Each item of food in the obento boxes represents a particular wish for the year. Traditionally osechi was prepared at home however these days the specially prepared boxes can be purchased in specialty stores, department stores and even some convenience stores. Family and friends celebrate together on New Year’s Day eating osechi ryōri, drinking beer and sake and celebrating the New Year!

Wishing you and your family a happy and healthy New Year!

We hope that 2021 brings back some normality and are here to continue to assist with any questions or quotes for future Japan travel plans.

Written by Rondell Herriot, Co-Managing Director Saizen Tours

Stay up to date with us on Facebook and our Website: